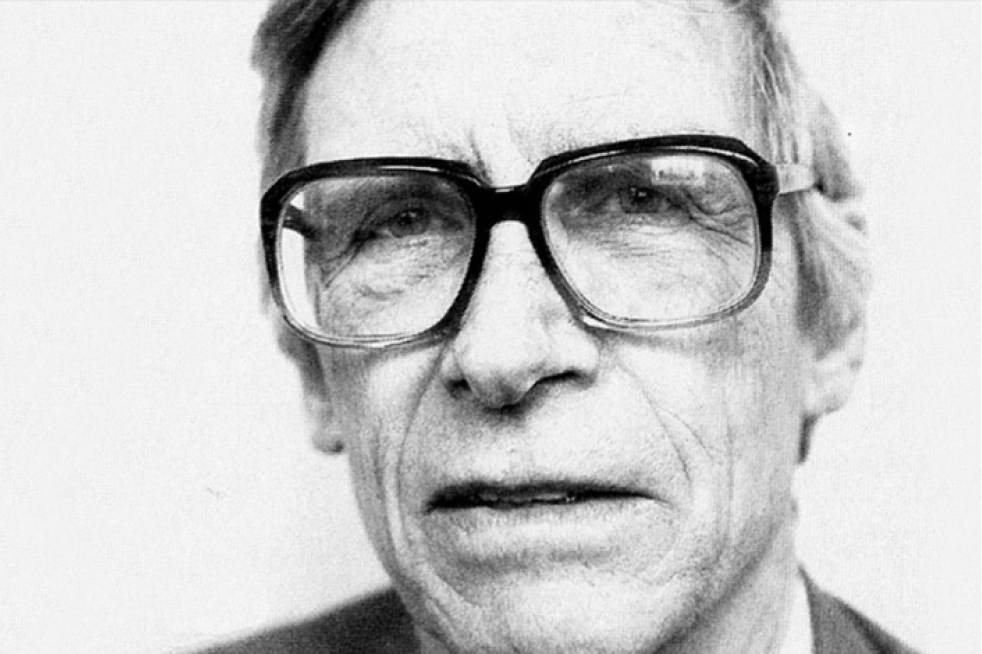

In the most prominent work of political philosophy in English in the second half of the 20th century, his 1971 A Theory of Justice, John Rawls’s goal was to justify the welfare state on the basis of a modernized version of the social contract theory. In his now classic treatment, Rawls justified an American form of European social democracy. His work was so methodologically careful and systematic that it reinvigorated the political theory of distributive justice and encouraged others to create their own systems throughout the 1970s. Many disagreed with Rawls, of course, but no political theorist afterward could ignore him. His became the most famous justification of progressivism, or welfare liberalism, in the late 20th century. After that, in his later book, Political Liberalism, he proposed to reject any comprehensive doctrine, including his early Kantianism, as a basis for liberalism. We will explore these two pieces of his view.

is that of distributive justice. The question is: What distribution of goods and services in society is just? Suppose you and a friend are walking and stop at a crosswalk. Waiting at the red light, you see a prosperous young man in an expensive convertible. At the same intersection, you see an apparently homeless man rooting through a garbage can. Your companion points and says, “Look at that. Is that just?” Well, is it?

We begin by defining the issue. In the mainstream political theory, a major issue is that of distributive justice. The question is: What distribution of goods and services in society is just? Suppose you and a friend are walking and stop at a crosswalk. Waiting at the red light, you see a prosperous young man in an expensive convertible. At the same intersection, you see an apparently homeless man rooting through a garbage can. Your companion points and says, “Look at that. Is that just?” Well, is it?

Note that there are two ways of approaching the question. One is to say that the sheer disparity of wealth between the two men is in principle unjust. Another is to say that whether the disparity is unjust or not depends on its history. How did each man get to this point? What happened in the past? Maybe the guy in the garbage can was rich but lost it all because of drugs. Then it might be just. Or maybe the rich guy stole his money, which would be unjust. The first is an outcome or end-state approach – just looking at the size of the disparity. The second—a procedural or historical approach. Progressives and socialists tend to take the outcome approach. Neoliberals and libertarians tend to take the historical procedural approach.

We’ve also seen that traditional utilitarianism can justify redistribution. The progressives use some version of utilitarianism and an organic theory of the self from German Romanticism. But the problem of utility, you may remember, is that it seems to justify violations of individual rights, and the positive notion of liberty seems to threaten similarly. On the other hand, deontological natural rights going back to Kant protect all individuals equally from harm, including protecting the rich from any attempt to redistribute their money to the poor to maximize happiness.

Harvard philosopher John Rawls gave his answer to the question with a theory he called justice as fairness. He proposed a new path. He begins with a deontological natural rights theory, and from it derives an argument for the welfare state over libertarianism, which he called libertarianism natural liberty. Rawls wants to advance the progressive agenda of views of people like Hobhouse and others, but he wants to use Kant, not Mill. He wants to use rights to get you to welfare. Rawls will accept the priority of the Right, with a capital R—that is, the rules of association—over the Good with a capital G—that is, any ultimate end or collective goal. Hence, neutralism— that is, for Rawls, government is supposed to be neutral with respect to the private notions of the Good—the aims and goals that you think will make your life meaningful are your business. Government just enforces the rules of association, or Right, which say what you can and can’t do you while you pursue your goals. At the same time, we will see Rawls tries to combine the procedural and outcome approaches. He tries to say on procedural grounds, rational persons would choose a partly outcome approach. The core of his theory is a new version of the social contract. Now remember the underlying idea. Those principles of justice are right which would be chosen by free, self-interested agents in a condition of equality. Now we’re going to have to look at three components of his theory. First, the original position—this is his version of the state of nature; then, the two principles of justice that he thinks would rationally be chosen in the original position; and then finally, the reasoning for those principles.

Rawls begins with a modern social contract theory. He admits there never was a state of nature in reality. Humans have always been social and political. But nevertheless, the idea behind the contract theory is right, he thinks. That rational, selfish people would choose a system is the test of the system’s validity, that it would be so chosen.So he asks us to imagine an original position—a hypothetical condition of equality among rational, self-interested persons, so accidents of social status will not influence individual choice or demographics – influence group choice. Again, these imaginary people are going to choose the principles of justice.

Now he posits the following constraints on them and their choice. There are some formal constraints. The choice will be a one-time only decision. No one can propose principles that no one else could accept. In other words, I can’t propose the principle “I gets everything.” And we assume that all find that certain things that anyone would need, whatever their theory of the Good might be—for example, income, rights, opportunities, et cetera. This is what he called his thin theory of the Good. Whether you want to be a drunk, a saint, or rich, you still have to eat, have to have housing, the right to choose your own life, et cetera.

More important, the individuals in the state of nature or the original position are instrumentally rational. That just means they’re able to pick what plan best suits their aims, and they’re mutually disinterested, or selfish. Except,he adds, they have to have some concern about some members of the next generation. Most crucially, they operate famously on what he called a veil of ignorance. That is, they have no knowledge of society or of others or even of their own selves that would allow them to infer where they might fall—individually fall—in any distribution scheme. This is what makes them equal in the state of nature. They don’t know how smart or strong or well- born they are, so they can’t tailor their choice of principles to their particular circumstances. If they could, the demographics of the original position would dictate the principles. In other words, people in the original position who think they’ll get rich in a free market will pick a free market. People who think they won’t will pick a welfare state. That biases their choices. With the veil of ignorance, I can’t predict how I’ll do. The result is I must make a selfish choice anyone else might make, but still on selfish grounds.

Since people often object to the veil of ignorance, let me spell out his argument for it. If we want to determine what distribution of wealth is just philosophically, we can’t do it by taking a vote in society now. Why? Because each rung on the income ladder will vote its self-interest. Well, you say, what’s wrong with that? What’s wrong is not the self-interest. It’s that the result will be determined by the historical accident of demography. A society with more poor than rich people will vote for a big welfare state. A society with a lot of rich people and a tiny group of poor will vote for a free market with no welfare state. We are philosophers. We want rational, self- interested people to vote, but we can’t let their actual, historical, accidental position in the socioeconomic distribution decide our philosophical answer.