We’ve completed our first pass through logical positivism, having paid special attention to the positivists’ doctrines of empirical meaning and of evidence. We’ve seen, in the positivists own attempts to explain and to improve their doctrines, the major problems that the view faces. And we’ve seen, especially in Quine’s work, at least some inkling of a rather different approach to these issues.

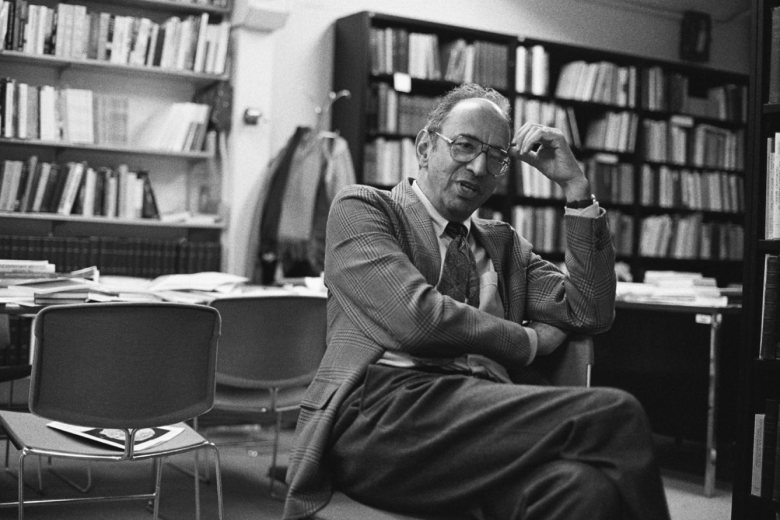

But the biggest blow to positivism came not from a philosopher at all—but from a historian of science. Thomas Kuhn’s 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a work of history that redirected the course of philosophy of science. I will often refer to it just as “Structure.” My instructors, when I was in college, told me this was the most important book published in the 20th century. I wouldn’t want to have to defend a claim like that, but it’s difficult to overestimate the importance of this book.

Kuhn had written his dissertation in physics at Harvard, though at the time, he was tempted to switch over to philosophy. While a graduate student in the physics program, he was recruited by Harvard’s president, James B. Conant, to teach in a new history of science course that Conant had devised. Conant’s intention was to convince talented students to become interested in science and technology. For Kuhn, history was a route back to the philosophical questions about science that were really his abiding interest. In Kuhn’s own words, he was “a physicist turned historian for philosophical purposes.”

Despite Kuhn’s longstanding interest in philosophy, Structure is—in one clear sense anyway—a history book. It tries to describe how science actually gets done. So, it’s worth taking some care to see how Kuhn’s project intersected, much less threatened, the project of the positivists. How exactly did Kuhn’s historical claims challenge established philosophical doctrines? There’s a puzzle there.

The positivists and Popper (though not quite in the same way) offered, as we’ve seen, rational reconstructions of scientific reasoning. We saw this in the positivists’ conception of theories as partially interpreted formal systems and in their characterizations of scientific reasoning as a kind of inductive logic.

Rational reconstructions try to make the reasons behind the methods, decisions, and practices of science, clear and explicit. In doing so, reconstructions ignore a lot of what actually goes on in science. This is not, by itself, objectionable. If you’re reporting on a business meeting, you’re going to ignore some of the false starts and confusions because that’s providing too much information, information that’s useless to your task, your report. What you’ll want to do is present the reasons for agreement and disagreement with the subject of discussion, not a blow-by-blow report of everything that was said. And at least if you’re offering a sort of serious, formal report, you’ll focus on what’s said, not on what you suppose the motivations behind what was said were. Gossiping might be a different matter.

Likewise, proponents of the rational reconstruction approach need not—and generally do not—deny that political, or economic, or religious, or psychological factors matter to the course of science.

But they think their job is to focus on the reasons, not the causes, of scientific behavior. So, this accounts for philosophers’ treatments of the history of science. They often ignore complications so that they can focus on the essential reasoning exhibited in the scientific episode under investigation. So, it’s not that they deny that Kepler’s being something of a sun worshipper might have been an important psychological motivation—and part of the explanation—of his switch to the sun-centered conception of what we now think of as the solar system. But they don’t talk much about it because they don’t think that illuminates the scientific reasons behind Kepler’s decision.

And this was appropriate, given the positivists’ and Popper’s conception of philosophy as an a priori discipline, one not having any distinctive factual domain of its own. There’s room for a “warts and all” description of actual scientific decision-making, but that’s not a philosopher’s job; let the historians go to the archives; let the sociologists or anthropologists walk into labs and describe what’s going on. Philosophers are to map out what we might think of as the space of reasons.

These philosophers were, nevertheless, committed to the idea that reasons are among the causes of scientific behavior. A rational reconstruction (an inductive logic, for instance) is supposed to have some explanatory value. Just as your reconstruction of the business meeting might leave some stuff out, but it’s supposed to explain how the decision got made—it might not be the whole explanation.

You’re not bringing in all of the prejudices that you think might have contributed, but it’s supposed to explain the reasons behind the decision that got made.

Likewise, the fact (if it’s a fact) that scientists follow a method or use a logic, as described by the philosophers, is supposed to be pivotal to the explanation of why science produces reliable, well-supported results, why it’s good at generating agreement among its practitioners, and why science is a more or less cumulative practice.

The rational reconstruction need not provide the whole explanation of the course of science—obviously. The method can’t much help you dream of a snake eating its own tail and then connect that to the structure of the benzene molecule.

Similarly, the underlying rationality of the scientific method is not going to be of much help in explaining various kinds of scientific failures and irrationalities; it’s the wrong sort of thing for that task.

But those aspects of science are to be explained quite otherwise, according to the positivists: for instance, by the fact that science is hard and that scientists are human beings who can let pride or prejudice impede their ability to do science well.

So, when Lysenko used ideology to ruin Russian biology for a generation, was he doing science? Well, he was a scientist, but he wasn’t behaving scientifically. He wasn’t following the method or the logic; he wasn’t living up to the norms of the enterprise in which he was participating.

It’s worth distinguishing, quickly, between norms and motives. Your reasons for playing chess could be to pass the time, to show how smart you are, to win money—whatever. But the norms of chess are, as it were, internal to the practice: They center on trying to checkmate your opponent. Your motives are external to the practice (you can do it for whatever reason you want); the norms are internal to the practice.

Popper and the positivists took themselves to be articulating the norms and goals internal to science. They took this to be quite different from investigating the motives of scientists.

So, these philosophers were not doing the history of science, nor were they pretending to do so. They insisted on a sharp distinction between empirical work and conceptual work—and a sharp distinction between descriptive and normative questions, between the “ises” of science and the “oughts” of science.

But, as we’ve seen, their project, nevertheless, made some assumptions about how science works, because they were confident that science—as actually practiced—exhibits the rational method or logic for investigating nature better than any other undertaking or practice does. And they further assumed it’s this fact about science that is crucial to the explanation of its success, the fact that it follows a kind of method or logic. So, they made assumptions about in what the success of science consists and about how the successes and failures of science are to be explained. It’s these assumptions that made them vulnerable to Kuhn’s attack.

It wasn’t intended as an attack. Structure actually appeared in a series initiated by, and edited by, the logical positivists. So, in that sense, it was kind of a Trojan horse. As will ultimately emerge, Kuhn shares some important doctrines with the positivists. But the differences are much more immediately important and much more immediately apparent, because Kuhn insists on mixing what the positivists had insisted on separating.

For Kuhn, the way to understand what’s special about science is not to investigate some underlying method or logic, but rather to look at the actual “warts and all” mechanisms by which scientific views have been adopted and modified.

This is because, Kuhn thinks, we don’t have a very good grip on the “oughts” of science apart from the “ises” of science. Our best theory about how to investigate nature is, itself, embodied in the history of the successful sciences—not in some philosopher’s conception of method. For this reason, Kuhn thinks history, and psychology, and sociology can help answer epistemological questions. We should look at how successful inquiry has been done in order to decide how inquiry should be done.

Kuhn was well aware of the charge that he was confusing empirical studies with normative ones. So Popper, for instance, claimed that lots of science was actually done as Kuhn described science being done, but that it was bad science that was done this way. So, on Popper’s view, philosophers (at least if they can get the methodology right) can tell us what counts as good science, and then historians answer the empirical question of, roughly, what percentage of the science that’s actually done is good, and what percentage is actually bad. This is a distinction between a normative question and a descriptive question that Kuhn rejects. He thinks those questions are deeply intertwined.

Part of Kuhn’s response to this charge from Popper and the positivists is going to have to wait until the end of this lecture, but part of it is pretty straightforward. Kuhn is placing his bets on the history of science, rather than the methodology of philosophers. If the philosophers say science should be done much differently than it actually is done, that’s a problem for the philosophers’ models, for the philosophers’ arguments, rather than for scientific practice.

Who’s done more for you lately? Who are you going to trust? What science has actually accomplished or what philosophers say it should be doing?

Kuhn’s got a strong initial position, anyway, but we should look at, as it were, the rules for adjudicating this kind of a dispute. It’s going to look good for Kuhn if he can offer an empirically rich picture that merits something like the respect we think science deserves, despite not being governed by anything like the philosopher’s rules of method. If he can preserve the specialness of science, then he’s going to score some points.

On the other hand, it looks bad for Kuhn if the “warts and all” approach to science turns out to be mostly warts. Imre Lakatos, a Hungarian philosophy of science who will receive our attention in Lecture Sixteen, complained that Kuhn turns science into mob psychology. So, if the historian can’t give us a solid reason for drawing an intellectually relevant distinction between the social practice of science and the social practice of spending a lot of money on the Psychic Friends Network, then we might want to go back to the positivist model, which says one of these practices follows a logic that the other one doesn’t—and the warts in science come from scientists who don’t live up to the norms of science.

As we play out this dialectical struggle, the outcome is likely to be somewhere in the middle. Kuhn is quite confident that a description of science as it’s actually practiced is going to deserve our intellectual respect, but it’s not going to give us everything that the positivists, with their method or logic, thought science could give.

It’s not going to be, for instance, a cumulative process that builds towards the truth. So, Kuhn’s notion of science is a practice that’s worthy of our respect—but is less, perhaps, distinguished than the positivists would have thought.

The history of science has developed enormously since Kuhn. When Kuhn came on the scene, it was a pretty simple discipline. Kuhn thinks that the sciences have an investment in the systematic misrepresentation of their history. They present it in a cumulative, triumphalist way. The right way for science to have proceeded is always, in retrospect, obvious (the apple falls on Newton’s head, he sees gravity, all is well).

Kuhn thinks the sciences have significant reasons for distorting their history (we’ll see those shortly). But this makes the history of science, Kuhn thinks, look a lot less messy and—for that reason—a lot less interesting than it actually is.

To take Kuhn’s favorite example, the sun-centered solar system of Copernicus was not opposed only by people who favored religion over science. The defenders of the Earth-centered astronomy actually had some good scientific arguments on their side. We’ve noted earlier their point about how the positions of the stars should change with variations in the Earth’s orbit, and that no observed parallax could be found. So, they had scientific arguments—not just, “the Bible says different.”

Kuhn goes on to describe the history of science as a kind of brainwashing—at least insofar as it’s taught to scientists by scientists. He says, “the member of a mature scientific community is, like the typical character of Orwell’s 1984, the victim of a history rewritten by the powers that be.” That’s a pretty cynical approach to the history of science.

But this approach has philosophical implications. The textbooks that scientists are taught from favor a broadly Popperian picture of science—full of heroes, and bold conjectures, and dramatic experiments like Eddington’s total eclipse experiment that verified, or at least failed to falsify, Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Kuhn admits that that kind of science happens (we’ll touch on it towards the end of this lecture). But he says if you want to understand science, you have to look at what most scientists do most of the time, and that’s not the heroic science of the textbooks. That’s what Kuhn calls normal science, and it works very differently than philosophers, especially Popper, had thought. In particular, normal science is a surprisingly dogmatic enterprise, according to Kuhn.

The title of Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, conceals the fact that a good half of the book is devoted not to scientific revolutions, but to this practice of normal science. And Kuhn has revolutionary things to say about normal science.

Normal science, he says, is governed by a paradigm. If you’ve heard that term a million times used a million different ways, it is, in fact, Kuhn’s fault; this book brought that term into common use. In fact, Kuhn himself misused the term quite regularly. One philosopher counted 21 different senses in which “paradigm” is used in Structure. I will try to clean up the terminology just a little bit.

As we’ll use the term, a paradigm is—first and foremost—an object of consensus. It’s big, and it’s agreed to. It includes the beliefs, the values, and the methods that—packaged together—constitute a way of doing science.

There’s a particularly important part of paradigms—exemplary illustrations of how scientific work is supposed to be done. Examples from the textbooks of how you solve a particular problem are of special importance for Kuhn. Kuhn, in the initial version of the book, confusingly called these key illustrations paradigms as well—but later, he distinguishes them from paradigms in the larger sense, and he calls them exemplars.

So, the science textbooks show you not how Newton messily arrived at his theory—but the finished product in a nice, clean form so that you can use it to solve problems.

A good scientific education, according to Kuhn, teaches you how to solve new problems using the theories you learn. The way it does this is by providing you with models that are designed to cover new cases. Scientists don’t learn a recipe, a set of rules, a logic, in the positivist sense. They learn concrete textbook examples, and they are trained to extend those examples to new cases.

This learning of models and how to apply them is a kind of indoctrination (and Kuhn uses the word “indoctrination”) into the other aspects of the paradigm: the paradigm’s standards of evidence, as well as its sense of what problems need to be solved. They’re not explicitly taught to new scientists, but they are implicit in the education—especially in these exemplars of what counts as solving a physics problem or a biology problem.

Paradigms thus generate a consensus about how work in the field is supposed to be done, and it is this consensus—not, as Popper thinks, perpetual openness to criticism—that distinguishes science from other endeavors.

Sciences coalesce (for the first time) around a paradigm. So to take one of Kuhn’s examples, prior to Newton, optics wasn’t so much a science as a pre-science. He calls it an “immature science.” There was too much disagreement about fundamentals (was light a kind of stuff or was it a state or modification of some other kind of stuff?).

People working in the theory of light were asking too many big, philosophical-sounding questions—spending too much time arguing with other researchers about fundamentals, rather than carrying on clear, cumulative research based around a common paradigm.

That’s how Kuhn would solve the demarcation problem. So, we see that he would be unsympathetic to the idea of something like Intelligent Design Creationism counting as science—because these people spend too much time arguing with people on the other side, and too little time developing a research agenda that asks and answers small, manageable questions rather than big, philosophical questions.

An immature science becomes a science once one of the competing paradigms scores a decisive victory, and most researchers in the field become persuaded that this picture of how scientific work should proceed is the right way to go.

And then the victorious paradigm writes history according to its own standards. It ignores what it regards as dead-ends and confusions— just as you ignore the dead-ends and confusions when you report on a business meeting. The new paradigm offers a rational reconstruction of the history of the scientific field.

So for reasons like this, says Kuhn, typically only one paradigm holds sway in a field at a time. Competition between paradigms leads not to science, but to philosophy of science (and that’s generally a bad thing for Kuhn). It leads to debates about how science should get done rather than the actual doing of science. The actual doing of science, Kuhn characterizes as puzzle-solving.

The paradigm identifies the puzzles, governs the expectations, and assures scientists that each puzzle has a solution, and then it provides standards for evaluating your own and other scientists’ solutions.

So, for instance, Newton’s theory tells scientists what kind of forces there are and how those forces are to be used to explain motion. It tells them what sorts of questions to ask and which problems it’s important to solve. So, it’s important to account for the motion of planets when they don’t behave as the theory says they should. It says, what do you do? Well, you look for some other body—say, a planet that’s not yet been observed—exerting a force on the planet that is misbehaving.

The paradigm also tells scientists what sorts of questions to ignore as irrelevant or unscientific. It was no part of Newtonian physics to reduce a force like gravity to a contact force, to a push or pull. It was perfectly fine to let this kind of mysterious force move instantaneously across vast stretches of time without any explanation of how it happens. That paradigm told physicists that their job was just to describe and predict the motion of objects, not necessarily to provide a mechanical explanation of their motion.

Here’s the biggest difference from Popper: For Kuhn, scientists are not testing the paradigm at all, much less trying strenuously to falsify it. They are assuming that the paradigm is right.

Normal science involves showing how nature can be fit into the categories provided by the paradigm. Most of this work is rather small-scale and somewhat detail-oriented. A scientist doing actual work—not the kind of work that shows up in a textbook, but day-today work—focuses on one small part of nature that has not yet been assimilated to the paradigm.

So, our paradigm might assure us that some genes in a bacterium turn other genes on or off without telling us the mechanism by which this happens. So, actual scientific work would involve running experiments to try to figure out how that happens.

If you do it right, it’s still not supposed to be earth-shattering. It’s not supposed to make it into a textbook for the next generations because the paradigm tells you more or less what kind of an answer to expect.

The work is creative, and it’s challenging, but it’s not dramatic or large-scale. It’s not easy to solve the puzzles of normal science, but the work gets carried on against a background that’s assumed to be reliable.

In saying that normal science consists in puzzle-solving, Kuhn is suggesting that it consists of problems that have solutions, and that all qualified participants can see and agree on the solutions. A crossword puzzle is a puzzle, not just a problem, because we know there’s a solution, and we know by what rules the solution is supposed to be reached. That’s why Kuhn chooses the term “puzzle.”

Similarly, the paradigm is testing scientists more than scientists are testing the paradigm. A failure to solve a puzzle is supposed to reflect on how good the scientist is at his or her job, not on the legitimacy of the problem. The problem is certified by the paradigm.

Normal science, then, is very unPopperian. It is much more dogmatic than it is open-minded, and it involves theories being preserved in the face of falsifying data, not rejected. The failure of fit between the paradigm and the world provides the bulk of the work of normal science.

But normal science, nevertheless, has an important Popperian virtue—it has a remarkable power to undermine itself. A scientific crisis occurs when a paradigm loses its grip on a scientific community. Crises, according to Kuhn, always result from anomalies. An anomaly is just a puzzle that resists solution, but if it continues to resist the best efforts of the best scientists for a long time, a crisis can result. Scientists can start to lose confidence that the paradigm knows how to handle a problem like this, an anomaly like this.

It’s noteworthy that Kuhn talks of crises of confidence. There is no crisis until it is felt in the community. This seems like doing psychology or sociology to the positivists. It’s very different from a logic or methodology of science. The judgment and feelings of scientific practitioners are built into Kuhn’s very notion of a crisis.

There’s no such thing as an unfelt crisis; it’s not a logical creature at all. It is in part for this reason that Kuhn rejects the positivists’ distinction between the contexts of discovery and the context of justification. The causes of scientific decisions cannot be sharply distinguished from the reasons for them.

This is true both of education into a paradigm and of the crisis that might lead out of a paradigm. Reasons don’t get their status as reasons just from logical space; they get them from the process of scientific education and crisis management, from historical space as well.

So, during a crisis, the rules of normal science get loosened, and it becomes legitimate to call the governing paradigm into question.

Science gets more Popperian in crisis times than it does in normal science times.

Paradigms are now being subjected to testing; they might get rejected. Scientists, Kuhn says, take an unusual interest in the philosophy of science. So, it’s not that Popper was entirely wrong about science. According to Kuhn, his mistake was to have taken crisis science to be normal science. Kuhn thinks science couldn’t accomplish what it has if it was in crisis all the time. If it was constantly trying to jettison its theories and arguing about fundamentals, it wouldn’t build what it builds.

Often, the crisis is resolved and people go back to good old, normal science. But sometimes a new paradigm may become ascendant—if that happens, a scientific revolution has taken place.

Kuhn chooses his political metaphors advisedly. A scientific crisis is like a constitutional crisis, and if a revolution occurs, it’s like a political revolution. There are no longer any clear standards of legality and legitimacy. Rational, well-informed people can differ profoundly about how science should proceed.

This is the part of Kuhn’s theory where people start to wonder about whether science is deteriorating into mob psychology. That’s our topic in the next lecture.

In this lecture, we need to close by fleshing out Kuhn’s answer to the charge leveled by Popper and the positivists, that what he calls normal science is just bad science.

His answer to this charge can best be explained in a locution from computer programming. It’s known as the “What you call a ‘bug’ is really a ‘feature’” defense. You say that this program doesn’t work— it’s got a bug. The guy who sold it to you says, “That’s not a bug; it’s a feature. It’s a good thing that the computer does this. You just don’t realize how good it is.”

Dogmatism, crisis, and revolution are not, according to Kuhn, failures of scientific rationality. They are, instead, enablers of scientific success. Normal science, in part because of its dogmatism, is beautifully “designed” (he doesn’t mean designed by anybody in particular) for generating anomalies and crises, but not too frequently.

As we’ve seen, a project in normal science is narrow but deep. It investigates one corner of the natural world very intensively. If there’s a failure of fit between the paradigm and the world, normal science is eventually likely to stumble on it, because it inquires so deeply. But the dogmatism of normal science ensures that the paradigm will be given a good chance to resolve this failure of fit.

The paradigm faces apparently falsifying data—but gets preserved and gets a chance to solve the problem. If we didn’t have a dogmatic confidence in our theories, we’d consider all of them falsified by a failure to fit with observation, and science would never get anywhere.

So, periods of crisis, sometimes followed by drastic rule changes, are good for science—as long as they don’t happen too frequently. Just as in politics, we want it to be difficult—but not impossible—to change the government. In science, we want it to be difficult to overthrow a paradigm that has worked for a long time, but we don’t want it to be impossible. We want a mechanism whereby the scientific community maintains confidence in the governing paradigm most of the time, but when certain problems start to look important enough (this is denying the discovery justification difference), when something starts to feel like a serious problem to enough scientists, that’s a sign—that’s evidence—that the paradigm should be re-thought and we should move from a dogmatic to a Popperian highly critical attitude to take with respect to our best theories.

So, what looks like a “bug” is really a “feature.” These apparent failures to live up to scientific rationality form a package that allows science to inquire deeply into nature, discover problems, and start itself over when the problems are threatening and far-reaching enough.